Current Temperature

17.1°C

Exposure to secondhand smoke causes weight gain, BYU research finds

Posted on January 14, 2015 by Westwind Weekly

By Karlene Skretting

reporter.karlene@gmail.com

Westwind Weekly News

New research is challenging the decades-old belief that smoking cigarettes helps keep you slim.

A BYU study published in the American Journal of Physiology: Endocrinology and Metabolism finds that exposure to cigarette smoke can actually cause weight gain. But here’s the kicker: Secondhand smoke is the biggest culprit.

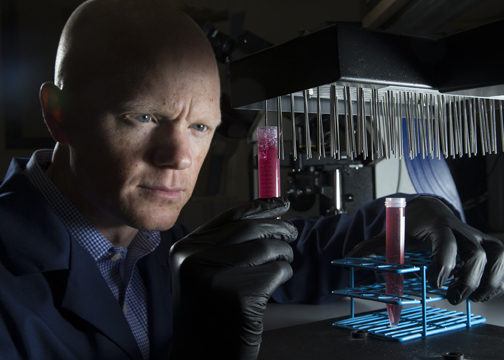

“For people who are in a home with a smoker, particularly children, the increased risk of cardiovascular or metabolic problems is massive,” said author Benjamin Bikman, professor of physiology and developmental biology at Brigham Young University.

Bikman was born and raised in Stirling, the small town instilled him with a good work-ethic and prepared him to compete competitively after high school. He has been employed by BYU for the last three years and was a big part of the year long study.

Data shows that about 15-percent of Canadian children live with someone that smokes in the home, regularly exposing them to secondhand smoke.

Bikman and BYU colleague Paul Reynolds’ interest in cigarette smoke is tied to metabolic function, they wanted to pinpoint the mechanism behind why smokers become insulin resistant. To carry out their study, they exposed lab mice to side-stream (or second-hand) smoke and followed their metabolic progression.

Sure enough, those exposed to smoke put on weight. When they drilled down to the cellular level, they found the smoke triggered a tiny lipid called ceramide to alter mitochondria in the cells, causing disruption to normal cell function and inhibiting the cells’ ability to respond to insulin.

“The lungs provide a vast interface with our environment and this research shows that a response to involuntary smoking includes altering systemic sensitivity to insulin,” Reynolds said in a press release. “Once someone becomes insulin resistant, their body needs more insulin. And any time you have insulin go up, you have fat being made in the body.”

The key to reversing the effects of cigarette smoke, they discovered, is to inhibit ceramide. The researchers found the mice treated with myriocin (a known ceramide blocker) didn’t gain weight or experience metabolic problems, regardless of their exposure to the smoke. However, when the smoke-exposed mice were also fed a high-sugar diet, the metabolic disruption could not be fixed. Now Bikman and his team are in a race with other researchers to find a ceramide inhibitor that is safe for humans.

“This may be the very beginning of developing a therapy to help mitigate the negative health consequences of someone that is forced to be around someone who smokes, it is quite gratifying,” expressed Bikman.

And what about the smokers themselves? Bikman said that one is easier said than done.

The smoker himself is in fact more exposed to the secondhand smoke than bystanders are, he went on to explain. Smokers are not safe from the health consequences; results apply just as much or more.

“They just have to quit,” he said. “Perhaps our research can provide added motivation as they learn about the additional harmful effects to loved ones.”

Or as funny as it may seem, in a culture so obsessed with body image, the threat of gaining weight may be more of a motivation to quit than killing their lungs.

“While they might know it is killing their lungs, you can’t see your lungs and it isn’t something you really appreciate. But if they know it is affecting their waist line, that is something that is more personal to people.”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.